Applying Scripture

Definition

Applying the Bible requires the skill and discipline to avoid incorrect as well as predictable applications.

Summary

Godly pastors have many options for applying the Bible. They look for direction in the Bibles commands, narratives, doctrines, songs and prayers. They also try to answer two or three of the four questions people ask when the speak. In this way, they bring Scripture to the people and the people to Scripture.

People say that the skill of applying the Bible is more caught more than taught, a result of instinct or spiritual insight and not methods. Yet most pastors struggle to apply the Word. Many believers hear the same applications, in roughly the same words, week after week: they should pray more, serve more, evangelize more; they should be more holy, faithful, and committed. This becomes predictable, hence, dull. If a teacher’s ultimate crime is to promote heresy, the penultimate crime is to make the faith seem boring. Many pastors dwell on the epistles or didactic portions of Scripture because they feel they only apply the Bible when they tell people what to do. As a result, they avoid doctrinal or narrative portions of Scripture.

There is a better way.

God-centered, Christ-centered Application of the Whole of Scripture

First, application is God-centered and Christ-centered. It begins with the work of God and our response to it. Therefore we preach and apply the story of redemption and the doctrinal passages that describe sin, repentance, faith, and union with Christ. These fuels proper responses to God’s truth.

Teachers resemble midwives. God gives people spiritual life without our aid, but we are God’s assistants. The work has these elements:

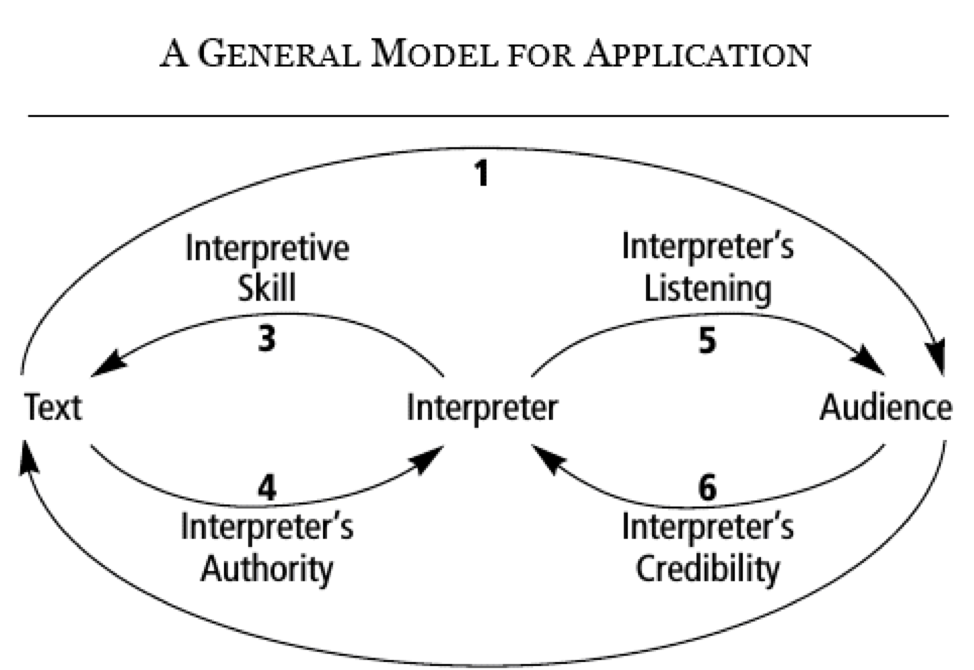

The primary elements in application are the text, the interpreter, and the audience. The interpreter is a mediator, taking the message to the people (arrow 1). The interpreter also takes the questions and needs of the audience to the text (arrow 2). The interpreter discovers the Bible’s meaning through interpretive skills (arrow 3), but Scripture is most effective when interpreters hear and heed its message (arrow 4). Interpreters speak most effectively when they understand and answer the questions people ask (arrow 5). Finally, when pastors love their people and show skill with Scripture, they gain credibility and their people listen (arrow 6).

Paul says “All Scripture is… profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2Tim 3:16-17). That means we should believe narratives, doctrines, songs, and prayers are as profitable and applicable as commandments.

Commandments often seem easiest to apply but they demand pastoral skills too. In the Pentateuch and the teaching of Jesus and the apostles, specific rules about oxen or sacrifices require interpreters to draw sound connections to contemporary life. And broad principles, such as “Honor your father and your mother” requires meditation. How does an adult believer honor foolish parents? Pastors will let the Bible’s various commands on this theme interpret each other.

More than one-third of the Bible is narrative or history and it is rich in application. Biblical narratives tell the story of redemption. Jesus said all Scriptures speak of him (Luke 24:25-27). The victories and defeats, the prophets, priests, and kings of the OT all point to Jesus. Clearly, the gospel narratives describe Jesus’ saving work. So narratives call us to faith, reveal the character of the God we trust and worship, and call us to him (Rom 8:29).

Jesus, Paul, and Hebrews all show that we should gain moral lessons from biblical history too. Jesus wants us to learn from the exemplary faith of people he meets and from people like David (Matt 8:5-13, 12:1-8). Paul treats David and sinful Israelites as examples to heed or avoid (Rom 4:6-8, 1Cor 10:1-14). And Heb 11 invites us to learn from the heroes of the faith.

The songs and prayers of Scripture teach us how to praise, confess sin, lament our troubles, and seek wisdom from God. They give us language to present the array of our thoughts and feelings to the Lord (see Pss 13, 69, 103).

Doctrine is relevant. Above all, doctrines reveal God’s character – his holiness, justice, love, mercy, grace, and faithfulness. Since he created us in his image and restores us in Christ, God’s character shows the character we should seek. Furthermore, we can apply a doctrine, such as the loving providence of God, by asking simple questions: “If this doctrine is true, what thoughts and actions follow?” Or “If I truly believed this doctrine, how would it shape my thoughts, emotions, and actions?” Doctrines also have great explanatory power. When we face life’s great questions, the answer often lies with a doctrine.

So far, we have considered how teachers bring the Bible to the people in application, but we now consider how teachers can start with people’s questions. The Bible, as well as the history of ethics, indicates that our questions about right living tend to fall into categories we can call “The four questions people ask.” Pastors can answer two or three of these questions in most messages.

Four questions people ask about Christian living

The first question is: What is my duty? That is, what should I do? What do I owe God and mankind? Second, who should I be? How can I become a person who habitually does the right, even in adversity? Can we gain the character to desire and do what is right? Third, what goals should we pursue? To what causes should I devote my energy? If we have good goals, we invest in worthwhile projects and find the means to achieve them. Fourth, how can we see? How can we gain insight, wisdom, or discernment to distinguish truth from error? How can we recognize erring voices, so we see the world God’s way and approach decisions correctly?

Many pastors feel they are applying the Bible when they tell people their duty, and they are! But discipleship entails more than obedience to commands. We also apply the Bible when we tell people who they are and how that should work itself out as they nurture the fruit of the Spirit. We also apply the Bible when we direct people to the right goals, so they pursue kingdom projects.

Laws set the parameters for right living, but we need more than laws. To do the good, one must be good. A good tree bears good fruit (Matt 7:18). A new heart or character, resting on faith and repentance, allows one to do good works. The heart, mind, and affections are the root of true obedience, obedience motivated by love. Law and duty are essential, but it’s impossible to state rules in enough detail to cover every situation. So we enter moral situations with several question, including: “What is the right moral decision? Am I seeing this situation correctly? Will I have strength to do what is right? Effective application answers all of these questions. Let’s further explore the four questions.

What should I do? Duty

Pastors focus on duty when they think the people need counsel or need to know what to do. The key question is “What does God require in Scripture?” Pastors especially address duty when their people face new or uncertain situations. The Bible states our duties in the law (Exod 20) and the prophets and in the teachings of Jesus and the apostles. Laws state the ground rules of life. Duties may be universal: everyone should tell the truth. Or they may be particular: carpenters make tables and pastors prepare sermons.

Duty can be attractive for the wrong reasons. Certain pastors like to sound authoritative and authoritarian leaders may seek control by laying down the law – and certain people like to be told what to do.

Who am I? Character

Pastors focus on character when they believe their people need moral skills and predispositions that will carry them down the right path for years in areas like work or marriage. Here pastors tell people who they are in Christ, explore how they might become more like him, and consider how people change so they experience a long obedience in one direction.

Christian living is more than doing right or wrong. It also touches the kind of persons ought to be. Christians of character believe right and wrong matters. They love the right, hate evil, and reliably do the right even under duress.

It is pointless to command a secular person, “Store up treasure in heaven” (Matt 6:19). Secular people inevitably store treasures on earth. Atheism annuls the capacity to obey. Likewise, nominal Christians resist Jesus’ teaching, “No one can serve two masters… You cannot serve God and money” (6:24). They think, “Why not?” So character creates the capacity to act on instruction. Who we are establishes what we can do.

Duty says, “Do the right thing.” Character says, “Righteous people do the right things.” Character is the architect of a way of life. It is open-ended. No one knows where a virtue like courage may lead. Courageous people act courageously, even if it costs them.

Character is essential because the law cannot fully map the Christian life. We find our way, we improvise, according to our character, in new situations and character creates strengths that let us improvise well.

Pastors address the heart or character because the ability to obey commands is more fundamental than the commands themselves. Why command people to obey when they cannot? One might as well order a drowning man to swim. Truly, he should swim, but he is incapable. Still, we cannot simply order people to change. Change begins when the Spirit quickens us, we believe, and we are united to Christ. Then, because God is at work in us, we work out our salvation with fear and trembling (Phil 2:12-13).

Character changes slowly, but we can grow in character. C.S. Lewis said, “Every time you make a choice you are turning the central part of you into something different from what it was before. Taking your life as a whole, with all your innumerable choices… you are slowly turning this central thing either into a heavenly creature or a hellish creature” (Mere Christianity).

Where should we go? Goals

Pastors focus on goals when they offer pastoral counsel to people who must choose between several valid options. What they do depends on where they are going, what they want to accomplish. Pastors then consider questions like “What is your life direction? What are the best means for achieving godly ends? Can you shape your corner of the world so it more nearly conforms to God’s plans?” As pastors teach the word, they help people discover what they want to achieve.

Goals are the causes and aspirations that direct our skills, energy, and choices. Goal may be small or large and life-shaping. Goals motivate us to train ourselves and seek positions and allies that let us fulfill our chosen projects. Goals explain why we work on one thing but not another. Pastors often help people choose and pursue wise goals. Good goals fit within the parameters of law and duty. We don’t help anyone pursue immoral goals.

Scripture clearly approves an interest in plans and goals. The Lord gave Moses the task or goal of leading Israel out of Egypt; Joshua led them into the promised land. Paul a goal – to preach the gospel foundationally, in places where Christ had never been named (Rom 15:20). We must test our goals, for God may not affirm them. David wanted to build the temple, but God ordained that Solomon take up that task, while David assisted him (1Chron 22).

When we pursue goals, we reflect the image of God, who makes and executes plans. The concept of spiritual gifts suggests that God has specific purposes for people. When we use our God-given talents, we accomplish goals joyfully.

How can I see? Discernment

Pastors focus on discernment when they need to help their people detect and resist false mindsets and customs and grow in wisdom. Pastors know that what people do largely depends on the options they can see.

Discernment is insight and understanding to see things as they are, from God’s perspective. Discernment lets us discriminate between biblical and unbiblical voices within the competing world-views we encounter. Discernment is the cousin of wisdom. If wisdom is skill in the arts of living, discernment is skill in the art of seeing. If wisdom is “the knowledge of God’s world and a knack of fitting oneself into it” (Bruce Waltke), then discernment is knowledge of the world and the ability to fit in or resist, as needed.

Discernment begins with fundamental convictions about God and the world. Core beliefs become the measure we use to test other ideas or perspectives.

David illustrates discernment. When Philistine and Israelite armies stalemated in the hills of Judea, Goliath offered to fight a hero from Israel and let that substitute for a full battle. Saul had promised his daughter in marriage and release from all taxes, but no one came forward because soldiers know: dead men pay no taxes anyway. They wondered who would dare to fight the giant.

David had the discernment to see the situation God’s way. He knew the question was not, “Who will dare to fight the giant?” but “Who is this to taunt the living God?” David saw that Goliath had despised God and declared “The battle is the Lord’s,” as he faced his foe (17:26, 42-48).

Discernment shapes our choices today. Take abortion. Some see the removal of a cluster of cells, the “product of conception.” Others see violence against the weak and defenseless. One sees women gaining control over their lives. Others see children losing their lives. Discernment enables us to resist conformity to our age. Community is essential, since most people are followers. They see moral situations as their culture does. Communities have customs and customs can gain moral force, for whatever is customary seems moral or right.

Bible application also includes discernment because a portion of an audience silently resists a pastor whenever he addresses controversial topics. If hearers reject the leader’s sense of the issues, they will also reject his guidance. Therefore, teachers address the world views of the day. Ideally, God’s word enables us to detach from our culture enough to see both its insights and its blind spots.

Thus, duty stresses what we ought to do, character examines who we ought to be, goals touch what we ought to seek, and discernment explores competing ideas about God, duty and character. Duties are definite, but our character, goals and discernment are open-ended. A man of character knows how he will act, but not where that may lead. A man who lives by goals know where he will go but knows not how he will get there.

So then, godly pastors have many options for applying the Bible. They look for direction in the Bibles commands, narratives, doctrines, songs and prayers. They also try to answer two or three of the four questions people ask when the speak. In this way, they bring Scripture to the people and the people to Scripture. By God’s grace, we may help our people grow into their identity in Christ.

Further Reading

- Daniel Doriani, Putting the Truth to Work

- Bruce Birch and Larry Rasmussen, Bible and Ethics in the Christian Life

- Richard Hays, The Moral Vision of the New Testament

- Jack Kuhatschek, Taking the Guesswork out of Applying the Bible

- Kevin Vanhoozer, The Drama of Doctrine

This essay is part of the Concise Theology series. All views expressed in this essay are those of the author. This essay is freely available under Creative Commons License with Attribution-ShareAlike, allowing users to share it in other mediums/formats and adapt/translate the content as long as an attribution link, indication of changes, and the same Creative Commons License applies to that material. If you are interested in translating our content or are interested in joining our community of translators, please reach out to us.

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0