It’s been 15 years since I moved to the land of citrus, sun, succulents, and surf, and I’ve put down new roots here. I love this place. But the longer I’m in California, the more I appreciate the Midwestern places that shaped me; the more my soul longs, in that Sehnsucht sort of way, for the Oklahoma and Kansas soil that first nourished me.

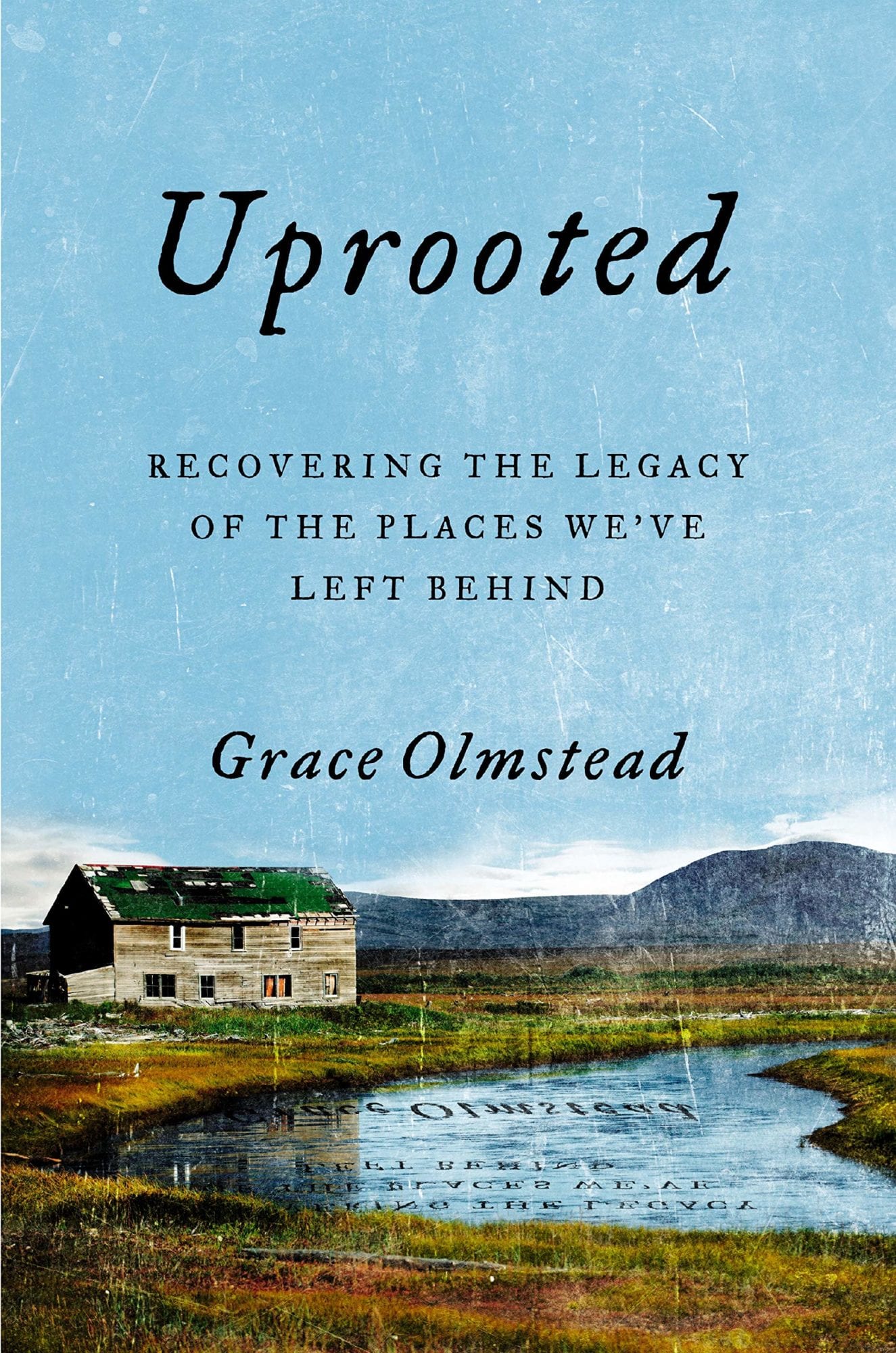

These feelings bubbled up with force as I read Grace Olmstead’s lovely new book, Uprooted: Recovering the Legacy of the Places We’ve Left Behind—a Wendell Berry–esque meditation on place, membership, and the complex ways ecosystems (whether farms or family or churches) thrive because of lasting commitments, or suffer for lack of them.

“Sometimes you don’t sense or understand your roots, how they make you what you are, until you’ve been uprooted” (8), Olmstead writes, framing the book as an exercise in discernment on whether she stays in her transplanted place (Virginia) or returns to her formative place (Emmett, Idaho). But while Uprooted reads in part like a memoir, it’s also a work of wide resonance. Indeed, it’s an urgent call to recover a love for the particularities of embedded locality in a world of homogenization, mobility, and disconnection.

Uprooted: Recovering the Legacy of the Places We've Left Behind

Grace Olmstead

Uprooted: Recovering the Legacy of the Places We've Left Behind

Grace Olmstead

In the tiny farm town of Emmett, Idaho, there are two kinds of people: those who leave and those who stay. Those who leave go in search of greener pastures, better jobs, and college. Those who stay are left to contend with thinning communities, punishing government farm policy, and environmental decay.Avoiding both sentimental devotion to the past and blind faith in progress, Olmstead uncovers ways modern life attacks all of our roots, both metaphorical and literal. She brings readers face to face with the damage and brain drain left in the wake of our pursuit of self-improvement, economic opportunity, and so-called growth.

Ultimately, she comes to an uneasy conclusion for herself: one can cultivate habits and practices that promote rootedness wherever one may be,

Olmstead, a D.C.-based journalist, weaves personal history with eye-opening reporting on troubling trends in American agribusiness and farm life. Uprooted thus has implications for political and economic policy as much as for our personal habits of connectedness—physically and spiritually—to the people and places we’ve been given. But it’s all connected. That’s one of the beautiful triumphs of this book, both in style and substance. It’s a sort of exercise in integral ecology that challenges readers to think beyond simple answers and partisan categories.

One of the beautiful triumphs of this book [is that it] challenges readers to think beyond simple answers and partisan categories.

Complicated in the way true love for place (rather than sentimental nostalgia) always is, Uprooted takes account of the broken and the bad alongside the beautiful. It’s not just an elegy for a time and place that will never be again. It’s a galvanizing call to commit and put down roots, wherever we are.

Why We’re Rootless

I thought about the movie Nomadland a few times as I read Uprooted. The film (read my TGC review) engages the American frontier mythology of restless wandering—in which open-road freedom and exploration take precedence over committed, stable involvement in a particular place. The movie captures the lonely sadness of a chronically rootless soul, resistant to the risk and potential pain of long-term belonging.

But Nomadland also captures the aesthetic appeal and romance of such a life. The world is large and beautiful—there’s always another bend in the river to explore, another vista to take in, another patch of soil to sample for a season. This aesthetic appeal is especially prominent in a diverse and wild nation like ours, where “on the road again” mobility and the freedom to pick up and start over elsewhere have long been esteemed values.

Throughout the book, Olmstead engages Wallace Stegner’s archetypal American categories of “boomers” and “stickers.” Olmstead says the boomer mentality of capitalist ambition—extract value from a place and then move on—has wrought spiritual, economic, and ecological havoc. Whereas boomers take from the land and move on, stickers “sow blessings in the soil for decades to come” (213). Stickers care as much as anyone about their economic well-being—but they see health as more holistic than merely maximizing profit.

And yet sticking is increasingly countercultural. Olmstead notes the foreboding generational attrition happening on America’s farms. Fewer and fewer farm-raised young people (who are best positioned to carry on the vocation) want to continue their parents’ work. They assume better economic opportunities are elsewhere. And so the best and brightest in rural America rarely stay there. But farm-raised boomers are just part of a larger story. Everyone tends toward rootlessness and restlessness today. We’re all lured by grass-is-greener prospects of life somewhere other than where we are. Why?

One major factor undermining our rootedness in tangible community and place is digital technology. Though Olmstead doesn’t comment on this in her book, it’s a huge factor contributing to our rootlessness. When we spend our lives increasingly on screens, in the business of a million distant places and “aware” of the (often embellished) exciting lives of distant connections on Instagram, we can’t help but become disenchanted with our proximate place and discontented with our people.

When we spend our lives increasingly on screens . . . we can’t help but become disenchanted with our proximate place and discontented with our people.

We can easily spend all our emotional energy each day invested in abstract online controversies, headlines from faraway places, and interactions with people we’ve never met offline—leaving us with no reserves of energy to invest in the people and problems in our actual homes and communities.

The virtual reality of internet space can become more enticing to us than the real reality of our physical place. No wonder we’re rootless.

Rooted Membership in Christian Discipleship

But rootlessness doesn’t lead to spiritual or material health. Not for individuals, and not for societies.

Though Olmstead doesn’t directly engage theological or church parallels through the concepts in her book, the applications are numerous. In this paragraph on the dangers of farming in isolation and the necessity of communal membership, you could change every instance of “farmer” to “Christian” and it still works:

The farmer needs neighbors. The farmer needs the church. The farmer needs associations, societies, and boards. The farmer needs mentors and mentees. When a farm community is working, it is neighborly and multigenerational. (184)

In both farming and in Christian life, individualistic, do-it-yourself autonomy is dangerous. We flourish in the Christian life when we acknowledge our interconnectedness with others. The body of Christ is an ecosystem of mutually enriching, interdependent parts not unlike a healthy farm. Consider this agricultural insight and its parallels to Christian community:

Roots absorb water and nutrients from the soil. They anchor and support the plant we see aboveground. But roots also are essential to the well-being of the soil itself—part of an intricate, living system we often ignore, because it’s down beneath our feet. (65)

The virtual reality of internet space can become more enticing to us than the real reality of our physical place. No wonder we’re rootless.

A Christian who puts down roots in a church community will be healthier. But so will the church community. As in subterranean soil, so in church: the intertwining root systems of a diversity of growing Christians creates a more fertile ecosystem for everyone. We need each other. And yet committed membership in a church community is an awkward and messy challenge.

“Membership—in marriage, in community, in place—is hard and sometimes painful,” Olmstead rightly observes. “It often requires selflessness and a loss of independence. It requires a whole lot of humility. But it is good” (196). Indeed, it is good. And yet the goodness of rooted interdependence is often not apparent until we learn how unsatisfying rootless independence turns out to be.

Rooted Plants, Not Tumbleweeds

A book like Uprooted reminds us that, in our spiritual lives as well as our economic and social lives, we aren’t meant to be tumbleweeds romantically blowing across the plains. Rather, we’re meant to be fruitful plants growing together in a garden.

Our roots are meant to be intertwined and ever deepening in rich soil—nourished by God (Ps. 1:1–4), bearing fruit, producing life, and cultivating order in our particular patch of Earth.

My patch is Santa Ana, California—a stretch of dense urban lowland sandwiched between the Pacific Ocean 20 miles west and the (occasionally snow-covered) Santa Ana Mountains 20 miles east. It’s a place of immense beauty and staggering brokenness. Bright bougainvillea and aromatic jasmine are plentiful, but so are homeless encampments. Jaw-dropping costs of living and other pressures make transience, not permanence, the norm here. Close friends are always moving away—looking for a simpler, cheaper life elsewhere. This was especially true in 2020.

But this is home for us. It’s where our people are. Our church. Our mission. Our membership.

It’s costly to be a sticker here, but Olmstead’s book reminded me why it’s worthwhile.