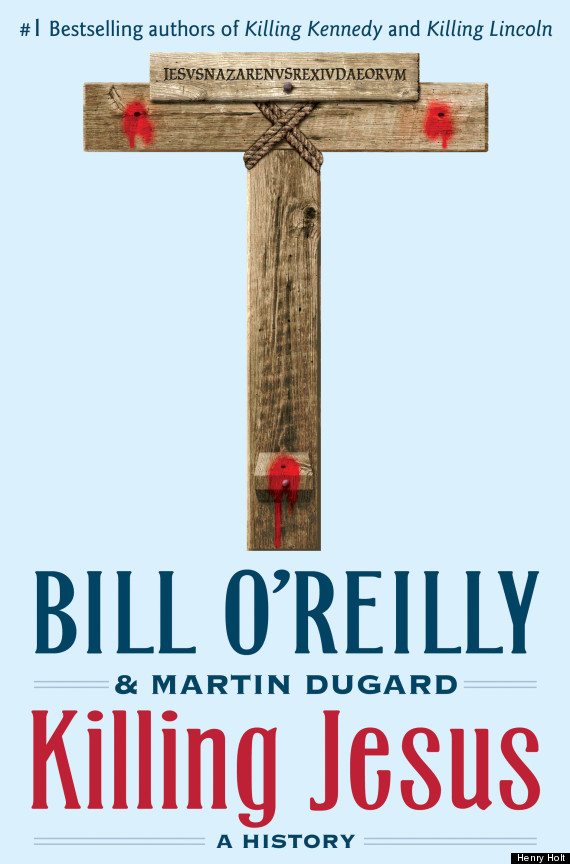

More than a century ago, Albert Schweitzer famously chronicled 19th-century Lives of Jesus in his volume The Quest of the Historical Jesus. Anyone perusing Schweitzer’s work—or the religion section in their local Barnes and Noble—will quickly realize there’s no end to biographies of Jesus. (They will also realize such works often tell us at least as much about the modern-day author as they reveal about the person of Jesus.) So when the dust jacket of Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard’s work boasts that Killing Jesus: A History tells the story of Jesus “as never told before,” one wonders: Can this claim really be true? You can decide after reading this review (if not the book itself).

This is now the third “Killing” book written by these authors (future possibilities are almost limitless). The first two were Killing Lincoln and Killing Kennedy, both New York Times bestsellers. Both writers are journalists, adequate credentials for producing the first two “Killing” books. But what is their theological pedigree? O’Reilly, anchor of the highest-rated cable news show in the United States, The O’Reilly Factor, and Dugard, a prominent history author, are both Roman Catholics but beyond this seem to have no formal theological training. They helpfully list their major sources at the end of the book (an excellent list, including many evangelical contributions). Still, moving from chronicling the circumstances surrounding the Lincoln and Kennedy assassinations to investigating what led to the crucifixion of Jesus is a major step up, as the authors acknowledge.

What kind of work is this? The authors claim it’s “a history,” meaning they tried to “separate fact from myth” (273) and to follow reliable historical sources. Miracles are not reported as having actually happened but simply as having allegedly occurred; for example, at one point the raising of Lazarus is simply called a “legend” (199). Roman sources are used extensively (and for shock effect), and the book typically oscillates between Roman and biblical history, with occasional flashbacks. Frequently a series of events or interchanges is taken virtually verbatim from one of the Gospels without any chapter or verse reference. There is no source documentation throughout the book (other than the aforementioned global reference to sources at the end), though there are helpful summaries of important background information in unnumbered footnotes. The authors follow the “Jesus of history”/”Christ of faith” distinction by relegating his messianic identity strictly to the time following his (presumed) resurrection.

Embarrassing Gaffes

A few embarrassing gaffes remind the reader that the authors are not biblical scholars or historians (though they have tried to research their subject). Among the more egregious errors is the claim that the northern kingdom of Israel fell in 722 BC to the Philistines (it should be Assyrians). Other claims are doubtful, such as that Jesus singled out four fishermen because people in that profession must be conversant in Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, and a little Latin. Even if it were true (for argument’s sake) that Galilean fishermen must be trilingual at a minimum, to argue this is why Jesus chose four fishermen as apostles is an argument from silence at best, since this is nowhere stated in Scripture. And how do we know Herod the Great had an inflamed big toe (11)?

Killing Jesus: A History

Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard

At times, the authors’ Roman Catholicism or possible political correctness rears its head. An example of the former is when they discuss the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox views on Jesus’ siblings and then state what “other Christian sects” believe—which apparently includes all religious groups not Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox. Also, Roman Catholic doctrine is simply reported without comment, including dogma on Mary and papal infallibility (265). Political correctness may be evident in comments on the part Jewish authorities played in Jesus’ crucifixion. O’Reilly and Dugard affirm that putting Jesus on the cross was Pilate’s responsibility (246). In one sense, this is true in that Pilate rendered the final verdict, but the statement lacks balance and lets the Jewish authorities off the hook a little too easily. The Bible says putting Jesus on the cross was the joint responsibility of Jewish and Gentile authorities (Ps. 2:1–2, cited in Acts 4:25b–26), and the Gospels show Pilate acquiescing to Jewish demands while the Jewish leaders press the charge against Jesus and manipulate Pilate to get what they want—Jesus crucified.

The authors begin every chapter with a precise location and date (e.g., Chapter 1: BETHLEHEM, JUDEA, MARCH, 5 B.C., MORNING). This is effective, and at places may be correct, but it does raise the question as to the accuracy of dates, particularly with regard to Jesus’ birth and crucifixion. The authors place the birth of Jesus in the spring of 6 or 5 BC, which is approximately accurate (fall may be more likely). However, regarding the date for the crucifixion, they only consider AD 27–30 but not what some view as the most likely date, AD 33. They settle on AD 30 and accordingly place the beginning of John the Baptist’s ministry in AD 26 and date the various chapters on Jesus’ ministry between AD 27 and 30. If AD 33 is the correct date, however, all those dates between AD 27 and 30 are wrong. In dating the beginning of the Baptist’s ministry to AD 26, the authors fail to deal with the information provided in Luke 3:1 that the Baptist began his ministry in the fifteenth year of Tiberius’s reign (ruled AD 14–37), which can hardly be AD 26 and is most likely AD 29 (14 + 15 = 29).

Readers may also be interested in the authors’ take on other commonly debated scholarly issues regarding the story of Jesus and the Gospels. They do not take a position on Matthean versus Markan priority, dating Matthew in the 70s (103). They include two temple cleansings, one at the beginning (John) and one at the end of Jesus’ ministry (the Synoptics). They hold to the apostolic authorship of John’s Gospel, though regrettably state that the phrase “the disciple Jesus loved” is an example of boasting and grappling for prestige and power (22) when more likely it indicates authorial modesty. Also, they repeatedly assert Jesus was 36 when he died (e.g., 251). But even if Jesus was born in 6 BC (rather than 5), he would have been 35 at the most in AD 30 (barely, if born in early spring), not 36, since there was no year zero.

Final Week

With regard to Jesus’ final week, the treatment is fairly conventional. The triumphal entry takes place on Sunday; the cursing of the fig tree and the second temple cleansing on Monday; dinner at Lazarus’s house on Tuesday; various questions by the Pharisees with Jesus’ response on Wednesday; the Passover and Gethsemane on Thursday; and the trial and the crucifixion on Friday. The authors inaccurately cite Annas’s involvement as an instance of illegality (but Annas does not pronounce the formal death sentence). They claim Judas betrayed Jesus to force his hand (a popular theory). They posit Jesus’ real offense is interfering with the priests’ commercial interests (there may be some truth in that).

Killing Jesus ends with the posting of the Roman guard and the women at the empty tomb.

The resurrection is relegated to an “Afterword,” which includes an interesting overview of the fate of the various characters in Jesus’ story (the twelve, Pilate, Tiberius, Caiaphas, Antipas, Roman-Jewish relations, and so on). This is followed by a personal “Postscript,” which is the authors’ attempt to highlight Jesus’ continuing effect on subsequent history, particularly American history (they mention George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Ronald Reagan). However, ending the “History” of Jesus with the empty tomb is deeply problematic. The biblical storyline makes no sense if Jesus didn’t rise from the dead—from a literary standpoint, the Gospels quickly get us to the road to Jerusalem, because that’s where the story is headed. So readers (and writers!) cannot remain ambivalent on the whole point of the story. As C. S. Lewis wrote, “You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon, or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronising nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

Fair and Balanced

Nevertheless, on the whole I was pleasantly surprised by this book. This is no Da Vinci Code! There’s much interesting and valuable information in the volume, mostly regarding the Roman background. O’Reilly and Dugard seem to try to be fair and balanced and to keep an open mind with regard to the sources and historicity. The book is readable and will no doubt find an interested audience. At the same time, this is obviously not a scholarly work and does not substitute for responsible academic research. In fact, the treatment of the Bible is fairly tame and unremarkable. The authors do not seriously grapple with some of the major hallmarks of Jesus’ ministry, such as his messianic identity, his claim to deity (e.g., the “I am” sayings), and his miracles, to name but a few. Also, they are highly selective in what they include, omitting most supernatural feats of Jesus and extended teaching portions such as the Farewell Discourse.

O’Reilly and Dugard state at the outset they didn’t set out to write a religious book but are only interested in telling the truth about important people. However, this may be easier to do with Lincoln and Kennedy (who didn’t exert any messianic claims or perform supernatural feats) than with Jesus. As it is, Killing Jesus only scrapes the surface of who Jesus truly was. The detailed recounting of lurid details regarding the moral excesses of various Roman emperors doesn’t make up for the lack of spiritual depth in probing the life of the most important person who ever lived. Because of his uniqueness, Jesus cannot easily be reduced to a one-dimensional portrait of a “historical” person stripped of his most essential attributes and calling. The reductionism inherent in such a quest renders this book, like its many similar forebears, of limited value in coming to terms with the compelling character that is Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah and Son of God.