Last month, the Christian Reformed Church (CRC) voted 123-53 to affirm that “unchastity” in the Heidelberg Catechism includes adultery, premarital sex, extra-marital sex, polyamory, pornography, and homosexual sex. The move wasn’t just an affirmation of biblical sexuality but also a call for church discipline for congregations that dissent.

You’d think, with numbers that decisive, that no one would be surprised by the outcome. You’d be wrong.

“No! Seriously! Only 53?” one woman tweeted, and she wasn’t the only one caught off guard.

“I was very surprised!” said Mary Vanden Berg, a Calvin Theological Seminary professor who was on the committee asking for the vote. “I had no idea there was that level of support.”

I was at the TGC women’s conference when I got the text from my husband. We’d been watching it closely—it felt like a watershed moment for the denomination we’d both been born into.

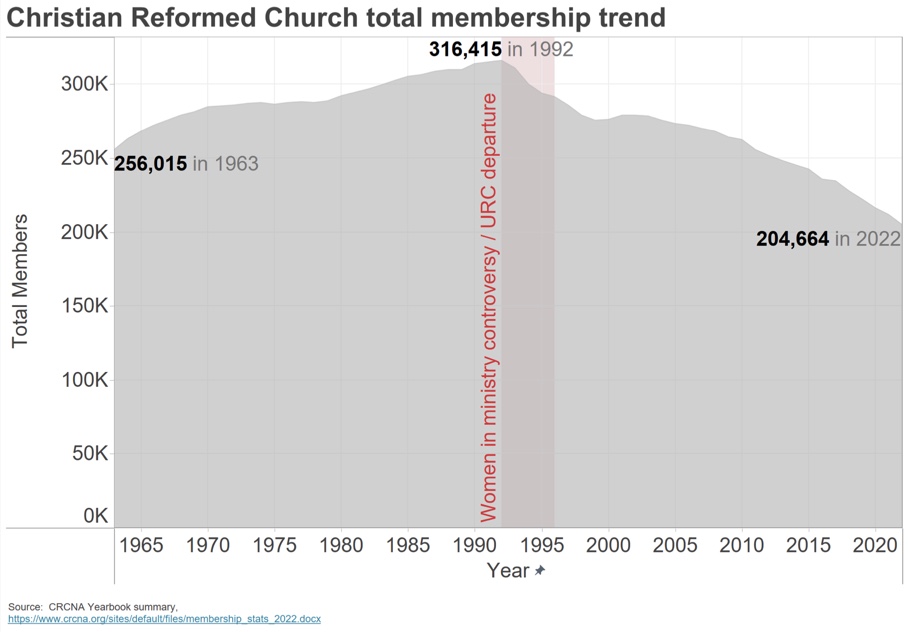

The CRC was founded in 1857, arising from a group of Dutch immigrants who split off from the Reformed Church in America over arguments about sound doctrinal preaching (the CRC said the RCA didn’t have enough) and accommodations to American culture (the CRC said the RCA was doing too much). Since then, the Grand Rapids–based denomination has grown—and then declined—to around 200,000 members in about 1,000 churches, and includes Calvin University and Calvin Seminary among its denominational institutions. It’s the third-largest Reformed denomination in the U.S.

Six years ago, a committee was appointed to wrestle through the church’s stance on sexuality. They submitted a 175-page report—in both English and Spanish—essentially clarifying and upholding the church’s historical teaching.

Honestly, I thought the delegates to synod (the CRC’s annual leadership convention) would vote to accept the report, but I had no confidence they’d affirm the confessional status of biblical sexuality and put church discipline behind it.

Five hours after the first vote, they did.

“They told Neland Avenue CRC to immediately void their appointment of a deacon in a same-sex marriage,” my husband texted.

I couldn’t believe it.

To me, the actions read like a sharp correction in a denomination where Neland’s ordination of a married lesbian deacon was done with “assistance from church advisers from Classis [Grand Rapids] East,” according to the church publication. Where a third of the faculty at Calvin University—the CRC’s flagship school—said this vote would hinder their academic freedom. And where just six years ago, a different report—one that allowed CRC ministers to officiate civil same-sex marriages—was submitted to synod.

The CRC’s sexuality struggle isn’t really news. As same-sex marriage was legalized and became more common, I’ve seen most denominations wrestle (and sometimes split) their way through sexuality debates. Even the leftward shift of the denominational leadership and educational institutions sounds typical for a lot of denominations.

But there are two things that stand out to me about the CRC.

First, it’s unusual to have a denomination on the path to liberalism yank itself around. It can be done (see the Southern Baptists) but it’s not normal (see the Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and even the Africa-heavy Methodists).

Second, statistics are clear that in America, the younger you are, typically the more liberal you are. Millennials and Gen Z are more likely to be comfortable using gender-neutral pronouns, believe same-sex marriage is good for society, and identify as LGBT+.

But at synod this year, it wasn’t the young people voting against biblical sexuality. Judging by those who stood up to share their views, it was largely the older generation asking for sexual inclusion and the younger crowd pointing back to the Bible.

What’s going on in Grand Rapids?

Watershed Moment

The last time the CRC had a battle this big was a generation ago. In the mid-1990s, after two and a half decades of committee meetings, synod effectively moved the denomination from complementarian to egalitarian. Reasoning that both views “honor the Scriptures as the infallible Word of God,” synod said each church could decide for itself whether to ordain women to church office.

“It was a watershed moment,” C. J. den Dulk told me. He’s been pastoring at Trinity CRC in Sparta, Michigan, for the past 32 years. “It changed the hermeneutic way of approaching Scripture. And a lot of people said if you change [the church ordinances] on women, homosexuality will come later.”

He could’ve left the CRC back then. A lot of conservatives did. In 1996, 36 complementarian churches with about 7,500 attendees left to form the United Reformed Churches in North America (URCNA). Over the years, more conservative CRCs have joined them. By 2021, the URCNA held 130 congregations with more than 25,000 attendees.

Westminster Seminary California faculty Robert Godfrey and Mike Horton were in that crowd.

“[A number of churches] decided that, at least from a human perspective, it didn’t seem that the direction of the denomination as a whole is going to change,” Godfrey said then.

In one sense, that was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Without the pull of a substantial conservative caucus, the CRC began to list leftward. Nearly 30 years later, about three-quarters of CRC churches ordain women deacons, and more than half ordain women elders. Synod said churches didn’t have to meet twice on Sunday, teach through the creeds and Reformed confessions, or wait for children to profess their faith before welcoming them to the Lord’s Supper. Students and faculty at Calvin University wrote about being pro-choice, openly queer, and welcoming and affirming.

But over time, something else was happening too, so quietly that it took me a while to find it.

What’s Going On: The Kids

If you watched the synod delegates speak, it sounded more or less like an even split between those for and against the codifying of biblical sexuality.

But what didn’t split evenly were the ages of those speaking. Often, those who argued for the welcome and inclusion of homosexual lifestyles had grey hair and wrinkles. Many of those who spoke for biblical sexuality were visibly younger.

I wasn’t the only one to notice.

“We’ve been seeing that over time,” said Chad Steenwyk, CRC pastor and chairman of the Abide Project, which formed in recent years to support the CRC’s historical teaching on biblical sexuality. Of the hundreds of church leaders associated with the project, most are in their 30s or 40s, Steenwyk estimated.

“It’s taken a while to raise up a new conservative generation,” he said.

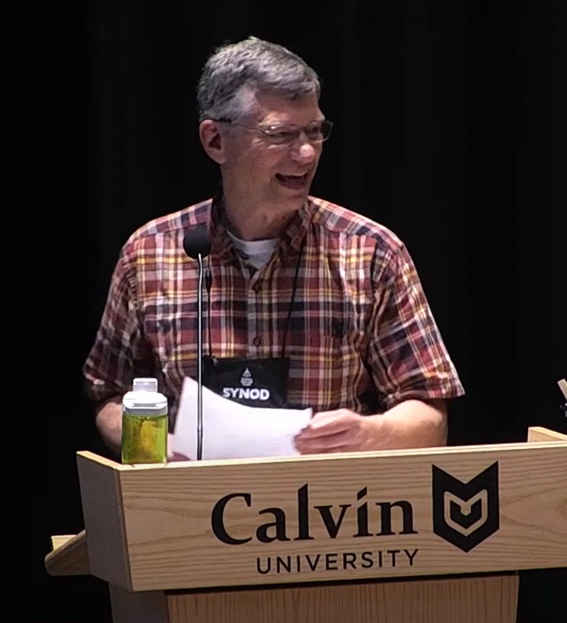

Some of those young pastors are coming from conservative seminaries outside the denomination—Reformed Theological Seminary, Covenant Theological Seminary, or Westminster Seminary California. Of the leaders at synod this year, president Jose Rayas, vice president Derek Buikema, and the chair of the advisory board for the human sexuality report Tim Kuperus are all Westminster grads.

Even Calvin Seminary, which is run by the denomination, has historically been more conservative than the university, Steenwyk said. (The seminary has not made a public statement on synod’s decision.)

Steenwyk also sees a lot of pastoral interns coming up through orthodox churches such as den Dulk’s. Over the years, den Dulk’s Trinity Christian Reformed Church has shepherded 18 interns. Five of them were from Westminster Seminary California, where den Dulk sits on the board.

“Another three of those interns grew up here at Trinity,” said Shaun Furniss, who pastors with den Dulk. “It’s not just a matter of pursuing [orthodox] prospects at seminary, but it’s also raising men up within the church.”

But can’t liberal churches and seminaries raise up leaders also?

What’s Going On: The Culture

In the seven years since Obergefell, American culture has embraced not only same-sex marriage but also a host of LGBT+ ideologies.

“I can’t make the same assumptions about marriage or sexuality that my grandpa could,” said Derek Buikema, vice president of synod and pastor at Orland Park Christian Reformed Church (where I am a member). Because of that, this year’s sexuality report was an improvement on the statement from the 1970s, he said. “It’s more conservative, more biblically sound—and more compassionate, broader, and more direct about the need for the church to love LGBTQ people.”

That’s because Christians today are less likely to take Scripture’s sexuality teachings for granted and more likely to have thought deeply about them, he said. “What does it mean to be a man? To be a woman? Is Scripture’s teaching good and beautiful? If so, I need to accept all of it. If not, I need to deconstruct.”

Children of both conservative and liberal churches walk away from the faith. But data shows that over time, mainline churches (which are more likely to be liberal) lose more members than evangelical churches (which are more likely to be orthodox). Former mainliners tend to either move to more evangelical churches or walk away from the faith altogether.

One could argue that the children of liberal CRCs are less likely to stick around or less likely to go into the ministry. But that’s hard to prove.

I gave it a shot, digging into the statistics to see which CRC churches had the most professions of faith—when those baptized as infants announce their Christianity to their congregations. If you ask the CRC for more detailed data, and then look at the top numbers stretching back to 2015, you’ll see a mix of liberal and conservative churches.

It’s true that in 2021, nine of the 10 churches with the most professions were associated either with Abide or with The Gospel Coalition.

But I don’t want to read too much into that—maybe those conservative churches happened to have a baby boom a while ago, and now those children are reaching an age to proclaim their faith. And even if the high school class of 2021 was extra orthodox, it doesn’t follow that they’d have a big influence on the 2022 synod.

Something else is going on.

What’s Going On: Ethnic Minorities

Back in 1996, about 5 percent of the CRC belonged to ethnic minorities. By 2011, that inched up to 8 percent. Today, it’s 22 percent.

Jose Rayas is one of them. A Hispanic pastor from Texas, he’s been a delegate to nearly every synod since 2004. He remembers looking around at the 2012 gathering in Toronto and seeing only three other Hispanic pastors.

So he started sending emails and making phone calls. Today, he’s the clerk of Consejo Latino, a group of 30 Latino pastors from all over the country. They’re working with the CRC to commission another 60 Hispanic pastors by the end of the year, most of whom will be church planters.

“We started having conversations about having people prepared to do the work at synod,” said Rayas, who ended up as synod president this year.

So the Consejo Latino drafted a statement.

“Our Latino community is traditionally conservative and attached to Scripture in each of the topics that it defines,” reads the statement, which was included in the synod debates. “The Old Testament prohibits adultery, incest and sex between individuals of the same sex, making it clear that only sexual activity within the context of marriage is pleasing to God.”

The Korean Council also read a statement at synod: “We agree with the biblical interpretation that the marriage between a man and a woman is God’s creation order and that other sexual acts, including same-sex, aside from this marriage, are sins.”

Likewise, the Navajo delegates spoke publicly in favor of biblical marriage.

Rayas pointed back to an overture in 2015 that called out several liberal churches for their participation in All One Body, an organization that argues for full LGBT+ inclusion in the CRC. Synod did not accept the overture.

The liberal voices “argued that what’s good for you might not be good for me,” he said. “In Consejo Latino, we saw that Scripture calls out the sinner regardless of whether they’re Hispanic or African American or Asian or Anglos. It calls out all of our failures and gives us hope.”

The ethnic minority voices matter, he told me, and they made a difference at synod 2022.

But he has another idea about what’s shifted in the CRC.

What’s Going On: Revival

For the past six years, Rayas has served on the human sexuality committee.

“There was a sense that we were working upstream,” said Calvin Seminary professor Matt Tuininga, who also served on that committee. Culture was affirming so quickly that “we worried our work might be meaningless—that by the time the report came out, it might be too late.”

The committee released a preliminary draft of the report in 2019 and then worried about how it was going to be received.

“We canvassed the classes [regional gatherings] for feedback, and we put it in a huge spreadsheet,” Tuininga said. “I was surprised—that feedback was overwhelmingly positive.”

Den Dulk was in one of those classes. He was also surprised.

“I remember saying [to the other pastors], ‘How many of you honestly thought the CRC would come out with a report this sound, this biblical, this faithful?’” he said. “And nobody there raised their hand. Nobody knew they would do it. We were like, ‘Thank you, God. This is so good.’”

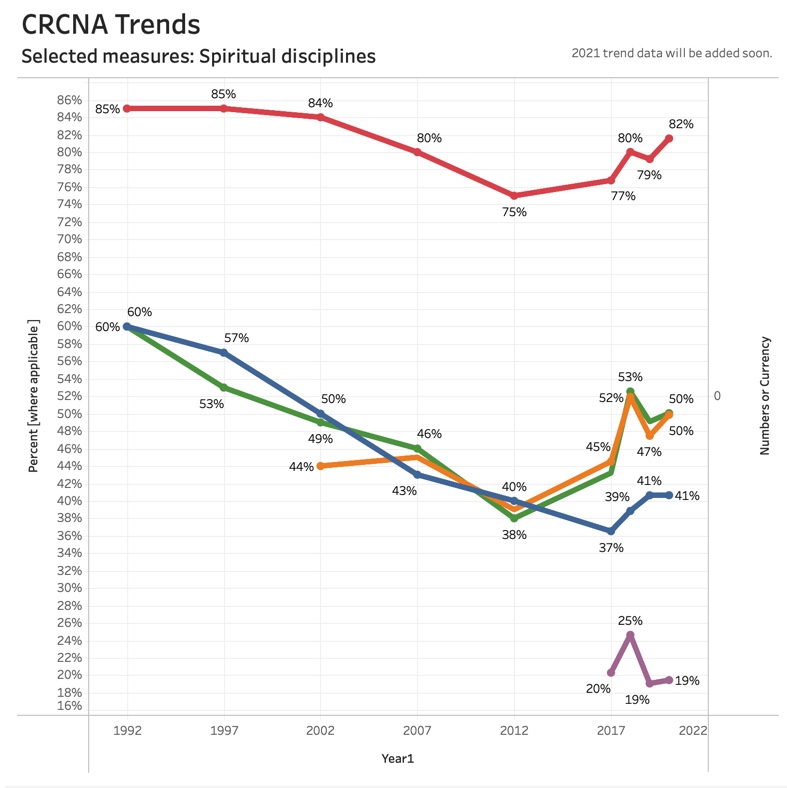

That mutual worry—of the committee and the churches about each other’s orthodoxy—wasn’t unfounded. Not only was the public face of the CRC moving left, but the spiritual disciplines of church members were on a 20-year slide. It wasn’t crazy to think most CRCers would shrug and prefer to let each church choose its own path on sexuality.

Instead, the committee and the congregations surprised each other.

And finally, clicking through the extensive statistics collected by the CRC over the years, I saw why.

So many of CRC’s trend lines are predictable, often mirroring general American stats. The CRC today is steadily more educated and wealthier and having fewer children than generations before.

But beginning in 2017, the quiet practices of personal piety have changed trajectory. The percentage of congregants who have been praying privately (red line in the graph below), having family devotions (blue line), reading the Bible daily (green line), and having personal devotions daily (yellow line) began to rise for the first time in 20 years. (The purple line is praying with a church prayer group.)

Another chart shows that the mean number of children in households with children—that is, the number of children among parents of childbearing age—also began rising around 2012.

This correlation makes sense to me. The connection between personal piety and favoring traditional marriage has been well documented. It follows that a denomination of people who pray, read their Bibles, and go to church would favor biblical sexuality.

Less clear is why CRCers began praying and reading Scripture more after 2012. There wasn’t an organized push for quiet times. The denomination didn’t campaign for Bible reading plans. The pastors I talked to didn’t even notice it was happening.

Those trends don’t follow the American trajectory. But we at TGC have seen this over and over among Reformed churches in other denominations over the past several decades.

Switching Churches

Two and a half years ago, my family and I began attending a new church. After visiting for the first time, I told my husband, “This feels like a TGC church!”

That’s because our new church has ESV Bibles in the pews, expository preaching from the pulpit, and a heart for church planting and missions. Those things felt normal to the members there—but to me, it felt like revival.

“There are a lot of factors to the way the Lord is moving within the denomination,” Steenwyk told me.

Tuininga put it like this: “It’s hard not to view what happened at synod as a grassroots effort, where the church woke up.”

Nothing Is Inevitable

The CRC didn’t solve everything in one vote, or even two. In the weeks since, Neland hasn’t removed its deacon in a same-sex marriage, instead appealing synod’s decision. Since no other CRC has appealed a synodical decision before, the denominational leadership is working out how to address it.

Questions have also been raised about Calvin University, where the day before synod’s vote, more than 140 faculty and staff asked that the statement “marriage is . . . to be a covenantal union between a man and a woman” be removed from the staff handbook.

Still, “this is more hopeful than I have ever felt,” Furniss said. The 70-30 percent split was clearer and more decisive than, say, a 55-45 vote would be.

“It’s easy to think that history or politics only goes one way, and liberalism is inevitable,” Tuininga said. “That’s a fallacy. There’s nothing inevitable about the future of the CRC or the UMC or the SBC or Roe v. Wade.”

Things ebb and flow, he said. “The pendulum swings. The challenge for us is to figure out our compass through it all.”

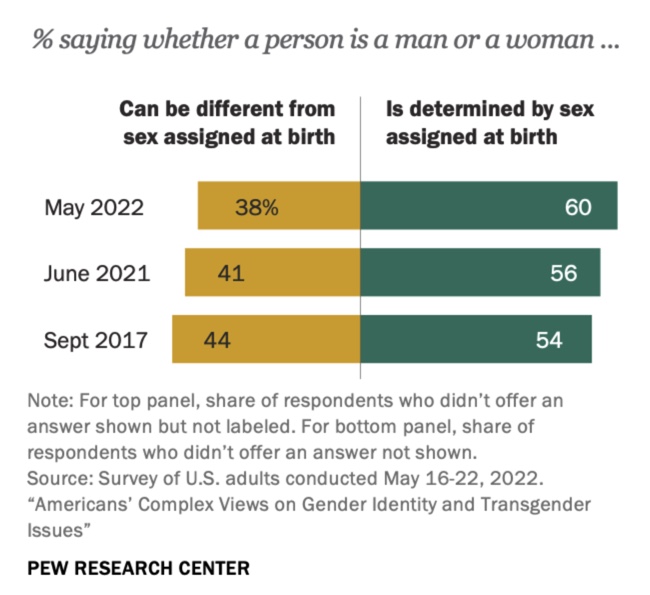

In America, the public opinion pendulum continues to swing in support of same-sex marriage. But transgenderism is stuttering—more people believe gender is determined by sex at birth in 2022 than did in 2017. Four in 10 say the pace of gender identity change is going too quickly.

In America, the public opinion pendulum continues to swing in support of same-sex marriage. But transgenderism is stuttering—more people believe gender is determined by sex at birth in 2022 than did in 2017. Four in 10 say the pace of gender identity change is going too quickly.

“The way ahead is to repent and believe the gospel, to grow in holiness and to contend for the faith,” den Dulk said. “There will constantly be false teaching. There will be more and more issues confronting the church.”

There will be stumbles. But by the grace of God, there will also be corrections.

“The good news is, whenever you honor God’s Word, he’ll pour out his blessing on it,” den Dulk told me. “God often gives warnings, but he also gives gracious rewards and blessings. I want to remind the CRC that they can’t fathom the blessings that will come on their life and churches. Yes, repentance is hard. But putting off the old and putting on the new—you couldn’t have a greater joy.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.